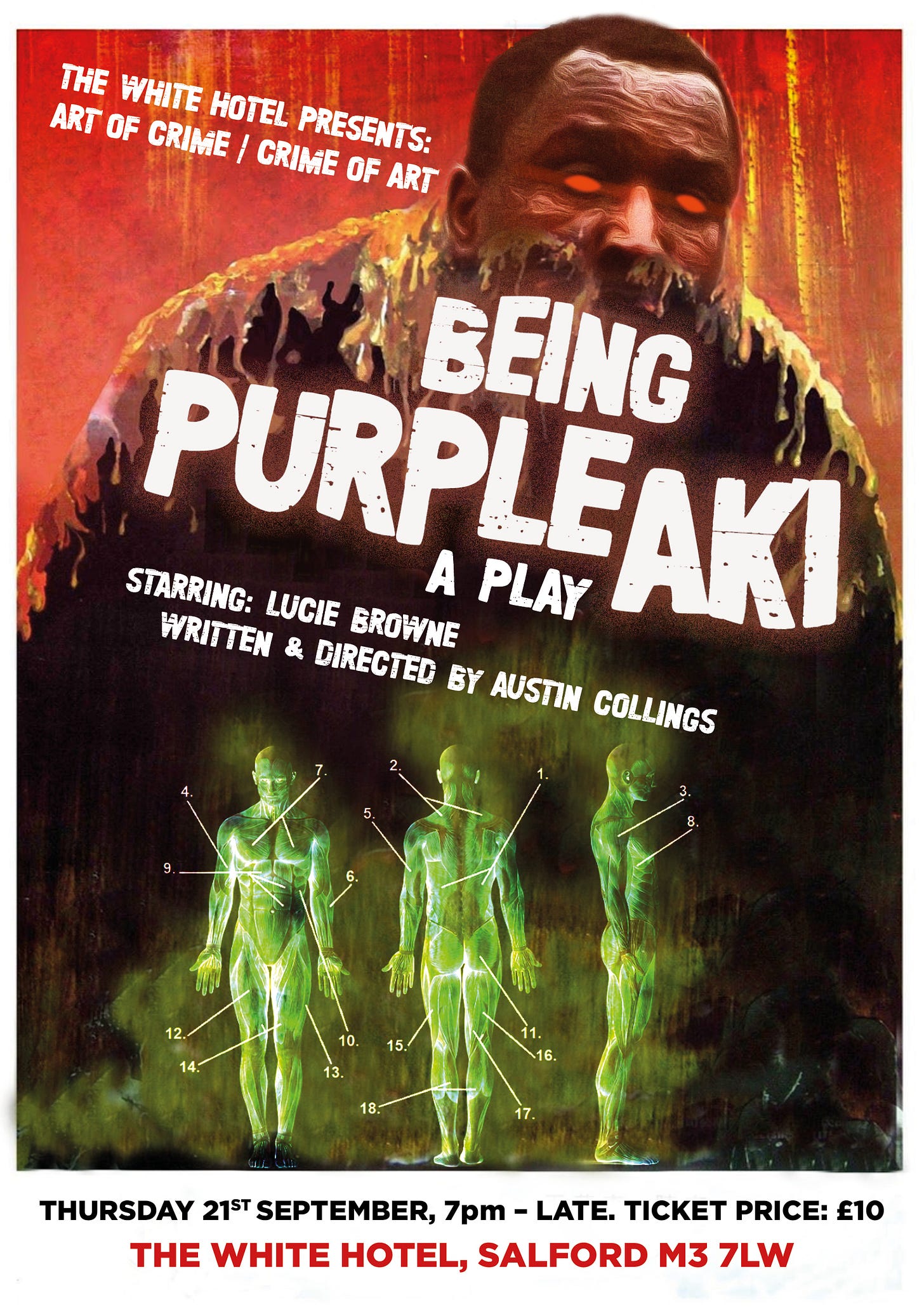

Being Purple Aki - A Play by Austin Collings

Staged at The White Hotel September 21st and 22nd 2023

‘The danger is that we will use our technology to become mutually unintelligible or insane if you like … you are a content machine. There is something seriously sick living inside of you. Stop. For all of our sakes but mainly for your own’ - VOICE NOTE 9, Being Purple Aki (2023)

Why do we struggle with reality so much now? More and more, those of us who spend hours of our lives on sites like Twitter (I’m not calling it that), Instagram, Reddit etc. find that our experience of the world around us is twisted into new shapes by social media, as if viewing The Real through a screen darkly. Baudrillard elucidated this condition best in his theory of Simulacra - to bastardise his point a bit (a lot), society has replaced its shared reality with an extended series of symbols and signs of which a construct like social media is just one piece. Think of how often tech investors and CEOs refer to online forums as ‘modern town squares’ or some such: they are mere copies of a concept that, somewhere down the line, might have been something real. It’s getting tough to argue that this distortion isn’t doing something strange to those who spend their days exposing themselves to it.

People don’t believe that things simply happen anymore. The five people who died on the Titanic submersible faked their deaths to escape the Illuminati. The person you’re sitting next to on a flight is a homunculus controlled by the matrix, open them up and all you will find are wires and circuitry. Everyone who dies did so because they ‘knew too much’, or they were vaccinated, every allegation of rape is made by an agent trying to tear down those whose podcasts pose a legitimate threat to the New World Order.

Into this breach comes the True Crime Podcast. Fulsome stories are shared of how podcasters have helped to solve decades-old cold cases [link], but less discussed is how our fascination with true crime provides the opportunity for sociopathic sensationalism. Anyone with a microphone and laptop can now tear open old wounds and dig around for content, or invent their own half-truths when they only find mundanity and regret.

That is the condition of Lucy/Aki Browne, the anti-hero and sole physical presence at the heart of Being Purple Aki, the latest play by Manchester writer Austin Collings, staged in late September at The White Hotel. The subject of Lucy/Aki’s investigation is Akinwale Arobieke, the man commonly referred to as ‘Purple Aki’: a 6’5” man from Crumpsall who became notorious throughout the North-West (particularly in Merseyside and the Wirral) due to numerous accusations of harassment that largely focus on young bodybuilders.

Growing up in the North-West, Akinwale was spoken about in terms that posited him both as a bogeyman and a joke, an excuse for lads on the playground to make lewd jokes about assault and harassment - ‘Purple Aki’s gonna get ya’, ‘heard you got bummed by Purple Aki’ and so on. The reality is that the charges against Akinwale mean he has spent a significant portion of the last 30 years in prison or subject to police restrictions on his activity.

Being Purple Aki asks us to examine why we may laugh about a subject like this, and how the ostracisation of Aki from society may reflect back on us negatively. It’s a delicate subject, the rendering of a negative feedback loop of victim and victimiser. Obsession pursues obsession down the digital rabbit hole.

Lucy/Aki Browne claims at the outset to be the elder sister of a 16 year old boy who died running away from Akinwale at a train station (in reference to the 1986 case against him), a fiction that is drawn into question as the play deepens its focus on the unreliable narrator and the contradictions begin to sharpen.

‘You’ve dropped yourself in it now’, one jeering commentator tells her. ‘In one post the railway tracks were wet. Now the sun’s out. Which one is it? Make your twisted mind up.’ Slowly, surely, the narrative shifts from what might have initially seemed like a joke at the expense of its subject to an uncomfortable examination of the behaviour permitted in the name of moral good online.

The laughter of the audience at a video of Akinwale being harassed by Scouse teenagers armed with fireworks begins to jar uncomfortably when we are told - as part of the recitation of a psychological report - that Akinwale’s muscle-touching obsession stems not from any perverse or sexual stimulation, but from ‘the desire for human contact’. His transgressions give those who want it carte blanche to make fun of the mentally ill, the lonely, and - crucially - those who look different. ‘Purple’ has always been a descriptor charged by racial hatred that has largely been permitted on account of its target, and Collings draws this into uneasy equivalence with, of all things, the massacre of the Branch Davidians at Waco: each are scapegoats deliberately ostracised from society, we are told.

The set is sparse - a low brick wall bisects the stage diagonally, a sleeping bag in the corner closest to the audience, the props are limited to cans of Vimto. At the denouement of the play - an absurdist wedding ceremony between Lucy/Aki and her ‘prey’ Purple Aki - the shutter of The White Hotel is thrown open to bathe the audience from behind in the light of the Manchester skyline, and silhouetted before it is Browne herself in a makeshift purple wedding dress. It’s a great bit of theatrical anarchy.

Collings has not produced a ‘cancel culture’ polemic - thank Christ - but a digital age parable that (mostly) treads around the pitfalls of writing about the online experience i.e. it’s rarely as obvious as, say, Charlie Brooker in the last ten years. Being Purple Aki is not uncritically cynical about the modern world (though there’s a fair amount of that going on); it asks for empathy, for understanding of the Other even when that understanding might seem undeserved initially.

Excellent review, really enjoyed reading it and I'll definitely try to see the play if I get a chance. Will say though - "less discussed is how our fascination with true crime provides the opportunity for sociopathic sensationalism" - hand wringing over true crime is really common, maybe the dominant mode of criticism of any format of the genre. And true crime should be criticized, and cheap, tawdry, and harmful depictions need to be questioned- but it's not like it's not happening (check any broadsheet review, social chatter, or comments section on a true crime property) now or previously (Bill James's Popular Crime digs into this).